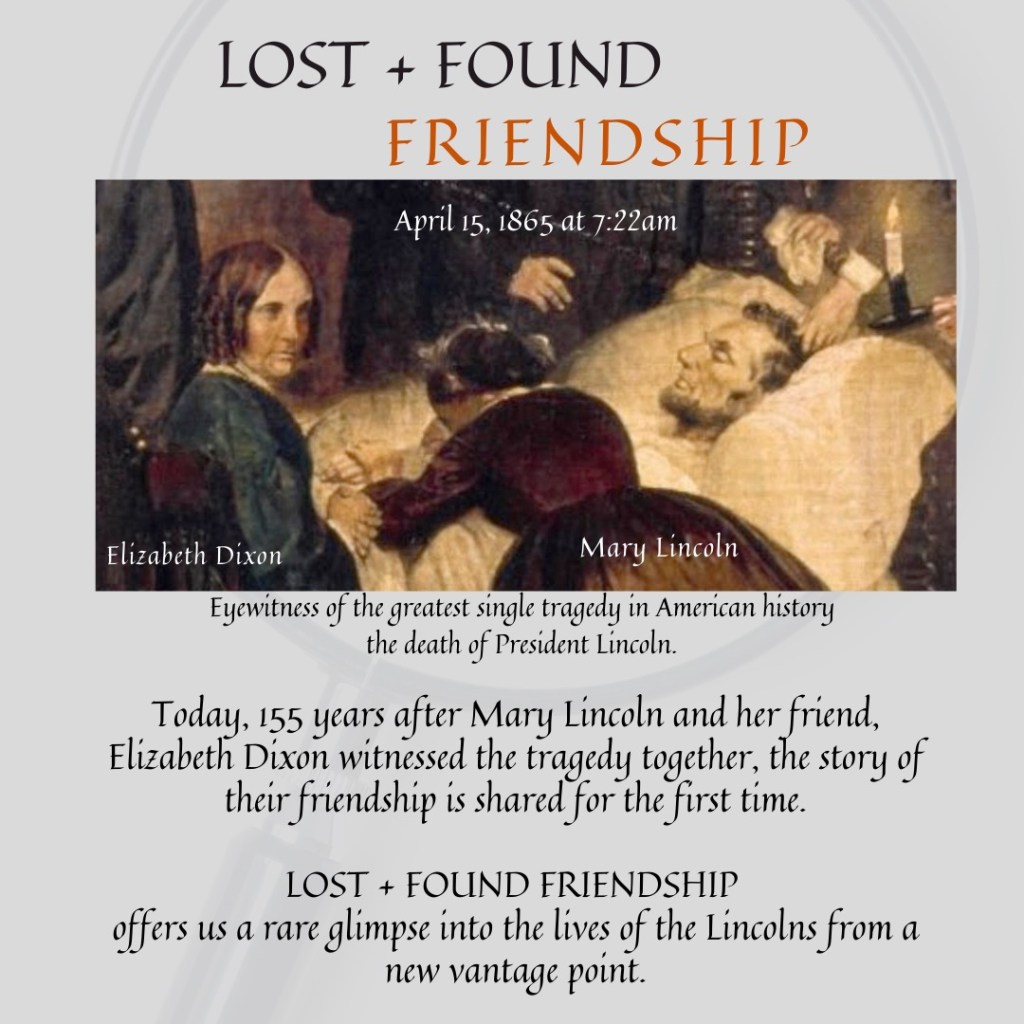

The Diary of Elizabeth Dixon, White House History, Issue 33

An excerpt from Diary of Elizabeth Dixon published in White House History, Issue 33, for Monday, December 15, 1845

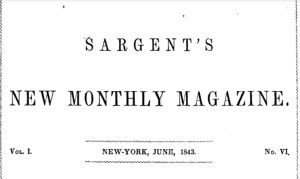

John O. Sargent spent the evening with us. Mr. Sargent is a brother of Epes who published my letter from Rome & the carnival in his magazine. 33.

Referring to the endnote for this entry —33: This account is “My First Day in Rome—Last Day of the Carnival” by a Lady of Hartford, signed E., Sargent’s New Monthly Magazine 1, no. 6 (June 1843), 251–53.

A quick online search uncovers * the short-lived magazine, Sargent’s New Monthly Magazine. In the June 1843 issue we confirm that Elizabeth Dixon had sent her account of her first day in Rome and last day of the Carnival to be published in Mr. Epes Sargent’s magazine. Only the editor and her close friends would know she had written the piece- instead she was “A Lady from Hartford”. This account of the 1841 Rome Carnival, taken from pages of her European honeymoon travel diary is the only known writing Elizabeth Dixon published during her lifetime.

“My First Day in Rome—Last Day of the Carnival” by a Lady of Hartford

We had hastened from Pisa to Rome, to be in season for the last days of the Carnival, when the revelry is at its height. There is nothing very interesting in the route, excepting the beautiful city of Sienna, with its cathedral of black and white marble, the floor of mosaic representing the life of David. The Italian language is here spoken in its greatest purity. The country is not remarkable for beauty, and the principal stopping place between Sienna and Rome, is situated on the top of an extinct volcano, whose sides are bare and brown.

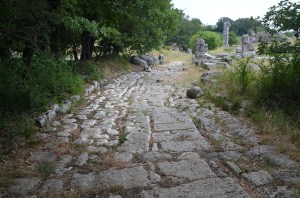

The roads are perfect, and we were whirled along with such rapidity, that on the third morning after we left Pisa, our eyes rested on the campagna of Rome.

This is a tract of uncultivated land extending for miles around the city, and uninhabited, save by a few poor shepherds, who may be seen here and there, in their picturesque sheepskin cloaks and slouched hats, with crook in hand, watching their flocks. They have a cadaverous appearance, for the campagna is infected with malaria, and may be called “the abomination of desolation.” Grass grows, and a kind of dwarf tree or shrub, but there is nothing like vigorous and healthy vegetation. There are some slight fences, probably lines of demarcation, and occasionally we passed an old tomb, a broken and ruined wall, but nothing that looked like a habitation for a human being for many miles.

The day was the 22d of February, the air was soft and warm, the green lizard was gliding about in the grass, or sunning itself on the fragments of ruins.

At last, we saw St. Peters, like a mountain against the clear blue sky, entered the Via Flaminia, and crossed the yellow Tiber. We had given our fancy flight through the past, and our minds were filled with the grandeur of the Caesars, when we were brought down to Modern Rome, entered the gates, and were stopped at the Custom-house, the common place of all travelers.

There is no more favorable view of the streets of Rome than from this entrance. The Piazza del Popolo with its great Egyptian obelisk, and fountains are before you; and beyond, the Corso, the finest street in Rome, extends as far as the eye can reach. On the left is the Pincian Hill, “terrace upon terrace, and rich in statues, cypresses and fountains;” next to it are the Hotels d’Europe and de Russie, built on the sites of ancient palaces, and palaces themselves, with their beautiful gardens. As we entered the city and drove to the Hotel de Russie, the Pincian Hill was covered with soldiers, marching down the terraces line after line, with helmets and bayonets gleaming in the sun, and troops of cavalry in gay uniforms and equipments, with their prancing horses. Martial music filled the air, and it seemed as if the old Caesars were yet alive, and we had come to witness a Roman triumph. The windows of the hotel were all open, the gardens filled with roses and violets which perfumed the air around, the delicious oranges and lemons hung in their dark rich foliage, birds were singing, and it seemed like the golden age of the world. We amused ourselves during the remainder of the day in looking out of the windows upon the novel sights, laughing at the dresses of the masquers, and occasionally receiving a bouquet or a present of sugar – plums, in the face, from some passing Punchinello, or it might be a greater character. In the evening some of our party attended a masquerade at the Apollo Theatre, but we reserved ourselves for the last great day of the festival.

The old adage “When you are in Rome you must do as the Romans do,” was on this occasion followed by us to the letter, and in the spirit too. Ours was one among the crowd of carriages, which followed each other in close file, up one street, and down another, from nine in the morning until after dark. Most of their occupants were masked or held before their faces small wire screens like sieves, to keep off the volleys of sugarplums.

Thousands of people on foot were dressed in as many odd costumes, according to their fancies, and were throwing bouquets and sugar – plume, or selling them to those in the carriages. Every one seemed perfectly gay and happy, and decidedly good – natured, for if a perfect tempest of bonbons were poured on one, the only way was to shake them off with a laugh and return the compliment. Indeed, our carriage was so full of voluntary contributions that we had to wade through them from one side to the other, and our path was literally “filled with flowers.” There were several steamboats on wheels (for the equipages were as odd as the inmates,) and when one of these was opposite, so slowly did they move, the pelting from all “the hands” was “pitiless” and quite overpowering. Before we started, we thought it must be great folly and become very tedious to spend a day in this manner, but we had not been through one street, before we found it was the most exciting amusement in the world, about as rational as any battle, and as some wiseacre remarked, “far less injurious.”

This sugar and floral warfare lasted till four o’clock in the afternoon, when a gun was fired to announce the commencement of the races.

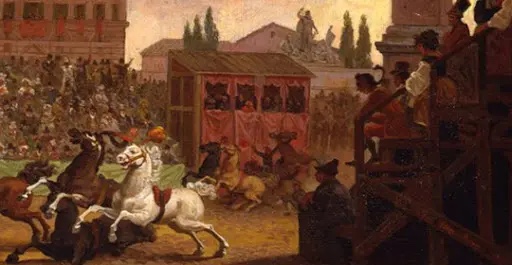

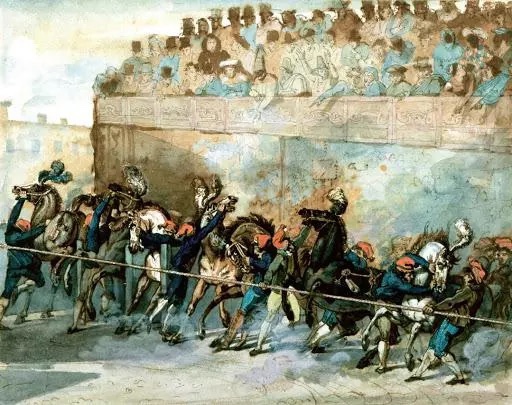

Our carriage fortunately drew up in the Piazza del Popolo, where the horses were to start. Around the obelisk, seats in the form of an amphitheater had been erected, which, as well as the streets, were densely crowded.

The houses through out the Corso were hung with drapery of scarlet, orange, green, and other bright colors, waving gayly in the breeze; the roofs, windows, and balconies were filled with heads, music was playing, and the shouting and buzzing of the crowd made the whole scene perfectly bewildering.

A second cannon was fired, and a phalanx of soldiers marched through the street, followed by a troop of horse, to clear the way for the principal actors in this scene.

A third cannon -and that great crowd were hushed into silent and almost breathless expectation.

Twelve small horses were led out to a barrier at the head of the street. They were so impatient that it was almost impossible to hold them; they seemed “to smell the battle, the thunder of the captains, and the shouting.”

They were decorated with cloth of gold, feathers, and ribbons, according to the taste of their masters. In a few moments a trumpet sounded, and, like winged creatures, they were in an instant out of sight.

The animals exhibited frightful impatience if checked or impeded in their way by the crowd, and woe to the unfortunate man, woman, or child who was the cause! A beautiful flag or other trophy was placed upon the head of the victor.

After the race, men came through the streets, selling small wax tapers and poles with fixtures for them, and it was every one’s duty to supply himself, and light them at dusk. Then what a curious scene there was! Every one trying to extinguish his neighbor’s light. It was as if the stars had come down and gone to fighting. This continued two hours and more, until the last Polyphemus had his eye put out, and then the crowd dispersed, to prepare for the masquerade later in the evening.

We went to Torlonia Theatre, which is very elegant and spacious. There are six tiers of boxes, and on this occasion the pit was covered with a floor for dancing. It was amusing enough to mingle with the crowd, and see the odd figures and costumes, nearer than in the daytime, and often to be accosted in one’s own tongue, by some being who looked as if he came from Pandemonium, perhaps in a scarlet dress hung all over with little bells, and great horns on his head, who would ask the most familiar questions about your affairs – and then to go up to the highest tier of boxes, and look down upon this motley assembly, which beggars all description, except as the oddest, funniest, and queerest of all scenes.

The night before, there was a tragedy as well as comedy. An Italian and his lady were accosted by an Englishman, who thought the lady was an acquaintance, and, after an unsatisfactory questioning and cross questioning, he ventured to raise the lady’s mask, but in so doing received a stab from her husband. The wound proved mortal, the Italian was thrown into prison, but it was decided to be a breach of law to raise a lady’s mask or veil, and he was liberated. Who shall say that the days of chivalry are past? The murder, for we can call it nothing else, occasioned a little commotion among the bystanders, but the crowd passed on, and all was forgotten.

Twelve o’clock arrives; and the whole carnival is ended. Religion takes the place of folly; and harlequin dresses are exchanged for sackcloth and ashes. E.

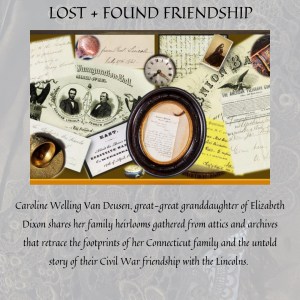

——————- This post shared new details about the life and writings of Elizabeth L. C. Dixon. My transcription of her 1845-1847 Washington diary was published in White House History, Issue 33, by the White House Historical Association. Below is a link to transcription:

* https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000080743200&view=1up&seq=9

The Diary of Elizabeth Dixon written during her time in Washington, D.C. Elizabeth often mentions the Kirkpatrick family of New Brunswick, New Jersey. She first visited them on her way from Connecticut to Washington.

The Diary of Elizabeth Dixon written during her time in Washington, D.C. Elizabeth often mentions the Kirkpatrick family of New Brunswick, New Jersey. She first visited them on her way from Connecticut to Washington.